A PILGRIM’S GUIDE TO THE GREAT AND HOLY MONASTERY OF VATOPAIDI 3

16 Ιουνίου 2009

In this connection it should be pointed out that because of the many adversities suffered by the monasteries during the 14th century, they were forced to adopt the idiorrhythmic system so as to leave the monks free to earn their own livelihood. However, they retained the institution of the abbot, whose duties were chiefly spiritual. The powers of administration were committed to the dikaios* of the monastery. The first Dikaios of Vatopaidi is encountered in a document of 1316 the priest-monk Niphon. After the office of dikaios, that of the sacristan was introduced. The latter managed the monastery’s property, while the dikaios now concerned himself with its affairs in the outside world. The monk Ignatius is the first Sacristan of whom we hear -in a document of 1633. In the year 1574, the Monastery was a-gain converted into a coenobium, on the initiative of Silvester, Patriarch of Alexandria.

Raids by pirate ships continued without abatement, resulting in the looting and devastation of the monasteries. Faced with this danger, Vatopaidi sought protection from Western princes, some of whom responded favourably, such as Alfonso, King of Spain (1456), William, Marquis of Monferrato (1512) and Francesco Morosini, Grand Captain of the Republic of Venice (1664). All of these issued orders placing the Monastery under their protection and threatening raiders with fines. Pope Eugenius, moreover, in a letter of 1439 urged Roman Catholics to visit the Monastery and support it financially.

The period of Turkish rule was one of many tribulations for the Monastery, one of the worst blows being that it lost a number of its metochia, which were expropriated by the Turkish pashas. In a firman* of 1516 the only metochia of the Monastery listed are: Pros-phorion (today’s Ouranoupoli), Ammouliani, Provlakas, Ormylia, St Mamas at Serres, Zavernikeia, St Panteleimon, Prinarion on Lemnos and some houses in Thessaloniki. Other documents of the same period mention the metochia of St Nicholas at Vistonida and of St Phocas in Chalcidice.

The loss of large numbers of estates and metochia reduced the Monastery to dire economic straits: in 1610 it owed 81,000 aspers* to the governor of Sidirokafsia. When the time-limit for payment had passed without the Monastery being able to pay off its debt, the governor sold to the monks of Pantocrator the kellia* called ‘Yiftadika’ for 71,000 aspers. Finally, Scarlatus Gram-maticus, steward to the Prince of Moldo-Wallachia, intervened and gave the Vatopaidi monks 70,000 aspers to buy back these kellia.

In this difficult period, the Tsars of Russia proved very helpful, as did the Princes of the Danubian Provinces, who ceded to Vatopaidi the monasteries of Golia (1604), Pretzista (1646), St Nicholas (1667), Barboio (1669) and Myrra (1689), as well as the sketes of Grazdeni, Fatatzouni, Kanitzou (1690) and Raketossa (1729). In the mid 19th century, the Monastery had some 45 metochia in Bessarabia with vast tracts of arable land, yielding income which in the last years in which they were held amounted to 26,800 Ottoman pounds. Unfortunately, however, the Monastery lost these metochia as well, since in 1863 Prince Cuza seized them and drove out all the monks.

Able fathers from the Monastery were sent to these metochia to rule them as their abbots and to manage their property. Some of them, moreover, were renowned for the virtue of their lives and for the influence which they exercised at the courts of the princes in the in-terests of the enslaved Greek race. The Ecumenical Patriarchate, in appreciation of their work, consecrated them bishops, their title being ‘Metropolitan of Eirenoupolis and Vatopaidi’.

The setting up of the Athonite School in 1748 was Vatopaidi’s greatest contribution to the interests of the enslaved nation. The building of the School and its operation were undertaken in full by the Monastery -at a period when it faced major economic problems because of the crippling taxation imposed by the Turkish authorities.

The founding of the School gave a fillip to the morale of the Greek world in its shackles, engaging the imagination and feelings of patriarchs and men of letters, so that Adamantios Koraes, in extolling the monks of Vatopaidi, wrote: «Felicitations, and again felicitations, most venerable fathers of Vatopaidi. Although you have paid what you owed to our homeland, it should thank you as benefactors and not as those who pay what they owe…» (Koraes, Parallel Lives of Plutarch, vol. A2, p. 937).

The Athonite School was the biggest Greek school in the Greek world under Turkish occupation, the number of pupils reaching 200. Its first headmaster was the deacon-monk Neofytos Kafsokalyvitis. In 1750, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Cyril V (1748-1757), issued a sigillium* in which he announced to the Christian world the founding of the School and sought financial support for it. At the same time, the Monastery sent to Thes-saloniki the priest-monk Joasaph with sacred relics to collect subscriptions for the School. After the resignation of Neofytos, the running of the School was taken over by the ‘Great Teacher of the Nation’ Evyenios Voulgaris, while the teachers included the deacon-monks Kyprianos Kyprios, afterwards Patriarch of Alexandria (1766-1783), Nikolaos Tzertzoulis and Panayotis Pa-lamas. Among the more famous of the School’s pupils were St Cosmas of Aetolia, the national hero Righas Ferraios, the scholar and writer Sergios Makraios, the educationalist losipos Misiodax, and the theologian A-thanasios of Paros. St Nicodemus the Athonite and Adamantios Koraes were among those who toiled to ensure its smooth operation.

After Voulgaris left, the School was never again to regain its former glory, with the result that around the year 1811 it ceased to function and during the years of the War of Independence, fell into ruins. Of these ruins, the only building to have survived down to the present is the Chapel of the prophet Elijah. A small school, however, continued to operate within the confines of the Vatopaidi Monastery to serve the needs of its brethren, with educated monks as its teachers. In 1821, the brotherhood of Vatopaidi made a last effort to convert their monastery into a coenobium. They communicated this resolve in a letter to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, seeking that a sigillium should be issued to this effect. However, the proclamation of the Greek Revolution intervened and the effort came to nothing. The Holy Mountain entered a fresh period of turmoil, which was to last until 1830.

To the national struggle the monasteries contributed their cannons, ammunition, and victuals, and turned their smithies to the production of weapons. One thousand, five hundred monks, led by the captain Emmanouil Pappas, drove the Turks out of Chalcidice. The Vatopaidi Monastery, on the request of the Holy Community, fitted out a ship with provisions and sent it to Provlakas in support of the army. The uprising was, in the end, a failure and the army was scattered over Mt Pangaio and in the trenches of Vigla.

The danger was now manifest, and Vatopaidi urged the other monasteries and the Holy Community to send senior monks as delegates to Provlakas to parley with the Turkish army. A large delegation, consisting of 120 senior monks, went to Provlakas and persuaded Abdul Rubut Pasha to negotiate, on condition that the monasteries should pay 1,500,000 piastres* as war reparations. Since, however, it was impossible to find so large a sum immediately, they asked the Pasha to accept 1,000 poungeia* as a prepayment and the rest by a given date. The Pasha accepted this arrangement, but held the 120 delegates as hostages. Of these, 82 were taken to prisons in Thessaloniki and Constantinople, where the majority died from illtreatment.

After this agreement had been reached, Rubut Pasha sent 3,000 troops to the Holy Mountain, headed by Murat Aga, in order to take charge of weapons and ammunition and to arrest the revolutionaries. The Turkish soldiers went from monastery to monastery, demanding food for themselves and their horses. The rest of the monasteries turned to Vatopaidi for help, asking for rice and barley and calling its monks their saviours. These tribulations of the Athonites came to an end with the withdrawal of the Turkish troops on 13 April 1830, the Sunday after Easter.

The years which followed, however, were no less difficult, and the Monastery fell into destitution because of heavy taxation and the loss of its metochia. It was forced to sell a large number of properties in order to pay off its debts; many of its metochia were illegally occupied by the Turks. All that was left were the revenues from the metochia in Wallachia and Bessarabia, and these too were confiscated by the Romanian State in 1863.

In spite of all this, Vatopaidi continued in more modern times to give generously to philanthropic causes. In 1880, the Monastery donated 3,700 pounds for the building of the Great School of the Nation and in 1908 gave the sum of 5,000 pounds to the Theological School of Chalki. In 1912, it undertook the building of the School of Languages in Constantinople.

In 1906, at the request of the Greek Consul in Thes-saloniki and the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the Monastery bought the Souflar metochi at Kalamaria, which then belonged to the Jew Jacob Modiano, so that it should not fall into alien hands. To the city of Thessaloniki itself, after the 1917 fire, Vatopaidi gave the considerable sum of 50,000 gold francs for disaster relief, and in the same year contributed what was for the time the large sum of 20,000 drachmas to the French Red Cross. In 1912, it redeemed from the Turkish Aga two villages in Chalcidice, Vrasta and Stavros, for the sum of 8,000 pounds. The Monastery’s philanthropic interests extended as far as Cyprus, where in 1860 it built a school in the village of Pedoula and in 1915 provided 1,000 pounds for the setting up of the ‘Vatopaidi School’ in Larnaca.

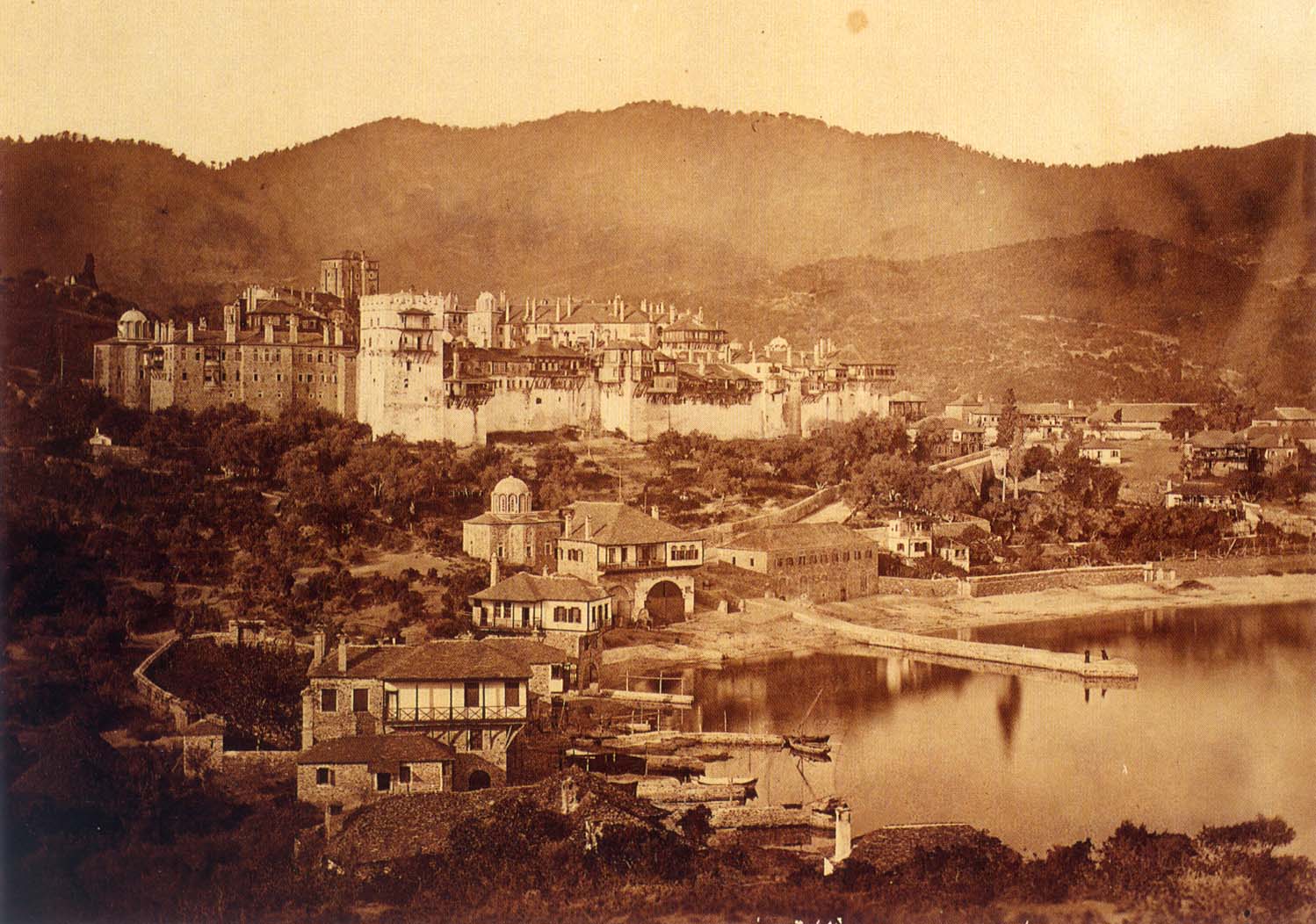

In June 1930, the work of the preliminary committee of the Orthodox Churches was carried out on the Monastery premises by representatives of the Autocephalous Churches under the chairmanship of the Metropolitan of Heracleia, Filaretos Vafeidis. In the following year, the Prime Minister of Greece, Eleftherios Venizelos, paid an official visit to the Monastery and was accorded a welcome of some grandeur. In his honour, the famous carpet, with the Monastery’s monogram and the double-headed eagle, stretched from the harbour to the main church. This carpet, measuring 700 metres, was made in 1913 for use during the visit of King Constantine to Mount Athos, a visit which never, in fact, took place.

During celebrations for the thousandth anniversary of the Holy Mountain in 1963, the Monastery was visited by the then Ecumenical Patriarch, Athenagoras, King Paul and other distinguished guests.

A decisive point in the Monastery’s recent history was its remanning in 1987 by a group of monks led by the elder Joseph Spilaiotis (‘the cave dweller’), from Aghiou Pavlou Monastery’s Nea Skete. Moreover, following a resolution on the part of the fathers of the Monastery and with a sigillium from the late Ecumenical Patriarch, Demetrius I, in 1989 the Monastery returned, after the elapse of centuries, to the coenobitic system of life. Archimandrite Ephraim was elected as first Abbot, and his enthronement took place on the Second Sunday after Easter (29 April) 1990.

To be continued…