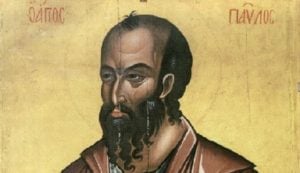

Saint Paul: the cornerstone of Western civilization (James W. Lillie)

28 Ιουλίου 2016

Saul, Hebrew by birth, Jew by faith, Roman by citizenship, Greek by education, and thereafter Paul, a Christian in outlook and in his heart, was the cornerstone of European and, by extension, the whole of Western civilization.

He regenerated and renewed the whole world, in fact. No other person has affected the course of human civilization, and even life on the planet, as much in the last 20 centuries. The great Paul, with the Greek language as his vehicle, united the East and the West, bringing from the East the message of the Sun of Righteousness, to bring people together, ‘that they might be one’.

And he did so not with some coercive, external, still-born political system, but through freedom and, above all, love, founding local churches wherever he went, despite the various trials and persecutions he faced. We read his words and they never fail to move us and shame us:

‘Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. Love never fails’.

From Homeric Troas, the Apostle of the Gentiles was called in a vision by a Macedonian, who told him ‘Come across to Macedonia to help us’.

And so, in the town of Philippi, he founded the first church in Macedonia, which was followed by others in Thessaloniki, Veria, Athens, Corinth and so on.

And ‘as if he had wings’, as it says in his Life, ‘he traversed the whole of the known world’, before meeting a martyr’s death n Rome.

But death had already been defeated, which was the essence of his teaching. To paraphrase the poet Andreas Empeirikos, the Apostle of the Gentiles made the victory over death the inspiration of life.

Arnold Toynbee, the philosopher of history says that Saint Paul captured Rome in a manner different from that attempted by Antiochus the Great of Syria. The new religion replaced the old, local gods of the cities with the Universal God of the hope of salvation for all humankind. This faith overturned the traditions of life and created new ones based on a wider perspective and experience.

First published in the newspaper ‘Makedonia’.

There are a number of things in this article which are easy to gloss over. For example, the author says, quite rightly, that Saint Paul used the Greek language as the vehicle for his teaching. Why would that be? Well, in the first place because, when he addressed Jews in the Diaspora, he would have had to do so in Greek. As early as the third century B.C., parts of the Hebrew Bible were translated into Greek for the benefit of Jews in the Diaspora who were no longer able to understand Hebrew. This version differs significantly from the Masoretic text (which was finalized in the 10th century A.D.), it is the one quoted most frequently by Saint Paul and is used in the Orthodox Church. For very many years, there was great opposition among Jewish scholars to any version other than the Masoretic, but today, younger Jewish scholars in Israel are doing very interesting research which reflects the fact that original text of the Old Testament has been lost and that there are a variety of other versions which have survived (the Septuagint, the Samaritan and so on) which reflect a different reading of the texts. To give a brief example, the Masoretic text has ‘The young lions do lack, and suffer hunger: but they that seek the LORD shall not want any good thing’; the Septuagint says ‘The rich have been made poor…’.

So in the first place, when he was talking to his own people abroad, Saint Paul would probably have used Greek for the most part. But he was invited into Europe by a Macedonian. And here we have a very important link. Macedonians were Greeks, despite what the snooty-and corrupt- Athenian lawyer and politician Demosthenes claimed[1]. At the time of Christ, Hellenistic Greek occupied a place not dissimilar to that of English in the modern world- a lingua franca, a common language. Indeed, it is known in Greek as κοινή (=’common’). This was because of the conquests of Alexander the Great. He, and more particularly his ‘Successors’, ruled Greece, the Middle East and Egypt[2] and made Greek the normal mode of communication in the Hellenistic world. Eventually, these lands were conquered by the Romans, but the common language remained Greek in Greece, the Middle East and in North Africa.

And so, at the time of Christ, Saint Matthew, as a tax-collector in the Roman Empire would have known four languages: Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek and Latin. It is almost certain that Christ, coming from ‘Galilee of the Gentiles’ would have known Greek, as His disciples must have done, some of whom had Greek names (Philip, Andrew).

This brings us to the next point; that Rome had conquered Greece but had been conquered by it. There were plenty of traditionalist Romans who raged against this development, but to no avail. When Julius Caesar was assassinated, his nephew, Octavian, the later Emperor Augustus, was furthering his education in Greece. Both the well-educated Roman aristocracy and the Jewish diaspora would have spoken Greek, otherwise why would Saints Peter and Paul have gone there? We read in the Life of Saint Paraskevi (26 July) that her parents were called Agathon and Politeia, both Greek names, as, of course, is Paraskevi itself. This does not necessarily mean that they were Greek, but they were wealthy enough to give their child a good education and encouraged her to read, which implies that that they had books. So it is fair to assume that, like most of the very early Christian population of Rome, they would have spoken and read Greek as a matter of course and that, even if they were not Greek, they were Philhellenes.

These were the kind of people that the Apostles would have won over to the new faith which, as Toynbee says, completely overturned the old ways and led to Western civilization.