Caesar and conscience (Fr. Patrick H. Reardon)

23 Σεπτεμβρίου 2016

Long accustomed to the thesis that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, it is not easy for Americans to think that governments may also speak with a higher authority. Indeed, the “consent of the governed” is so commonly withheld these days that it may pass as part of our birthright.

For the same reason, it is difficult for Americans to believe that the art of government has any necessary relationship to a higher order at all, such as the order of the moral law. So clearly have we come to distinguish legal concerns from moral concerns that a real separation of the two is pretty much taken for granted. Anyone today who says that “you can’t legislate morality” is understood to be voicing a truism.

We may seem terribly bold, therefore, when we say that we politely disagree with this perspective. We do so, nonetheless, and we do so for the sake of what the Bible tells us.

The Christian submits to civil authority, St. Paul says, not only because civil authority has the power to exact that submission, but also “for the sake of conscience” (Romans 13:5). In view of Paul’s high respect for conscience, his assertion that submission to civil authority is a conscientious concern is truly remarkable.

Conscience (syneidesis), a word that Paul uses seventeen times in his epistles, refers to man’s inner light, the faculty by which he discerns moral differences and directs his ethical decisions. Paul’s use of this word contains, in addition, the sense of “consciousness” and pertains to the reflecting self-possession of the moral person (Romans 2:15; 2 Corinthians 1:12). It designates the critical moral discourse that man conducts within his mind (synoida). It refers to his human intentionality, his transcendent capacity as a conscious moral agent.

The Christian’s conscience, therefore, is the necessary and inseparable companion of his faith. It is to man’s conscience, his reflective faculty of cognitive intention, that the gospel itself is addressed (2 Corinthians 4:4; 5:11), and it is conscience that receives the witness of the Holy Spirit (Romans 9:1).

When Paul appeals, therefore, to the conscience with regard to civil authority, he exalts political responsibility to a very high order, recognizing that the Christian stands within a social context of grave and radical obligations. For the Christian, that is to say, political responsibility, including civil obedience, is not optional. He can flee from the responsibilities of the political order no more than he can abandon his own humanity, for the first are necessary components of the second.

For this reason also, man’s relationship to civil authority has to do with his relationship to God. It pertains to those essential matters about which every conscience is finally answerable to the Judge of history. Although the things of Caesar are not to be confused with the things of God, God himself requires that to Caesar be rendered his due, and that conscientiously.

Consequently, disobedience to civil authority is no light thing and never warranted except for the sake of conscience itself. What is commonly called “civil disobedience,” therefore, must not degenerate into a form of political fun and games. It is a very serious undertaking, and in order to be morally legitimate, such disobedience must express a stern dictate of conscience and never be employed simply as a mechanism of political influence. Christian history provides the most obvious examples of conscientious disobedience in the lives and deaths of the martyrs, who refused to put Caesar in the place of God.

For all that, Caesar appears to stand—if one may say so—uncommonly high, at least in the eyes of St. Paul. He is called “God’s servant,” and, in principle, whoever resists Caesar “resists what God has appointed.” Those who do so, moreover, “will incur judgment” (Romans 13:2,4). We do well to remember that the “Caesar” under discussion here in Romans was Nero, and that these lines were penned by a man that Nero put to death.

Government’s proper maintenance and sanctioning of civil life, then, precisely because it relies on and serves the moral order, properly addresses the Christian’s conscience. It is significant that both times when Paul uses the word “conscience” in the Acts of the Apostles, he does so in a judicial context, once before the Sanhedrin (23:1) and once before a Roman governor (24:16).

Another important inference is to be drawn from these considerations about conscience and the civil order, and St. Paul does, in fact, draw that inference. If civil government truly acts as “God’s servant,” then the political order can hardly be amoral, or morally neutral. On the contrary, the Apostle regards civil authority not only as subject to the restraints of the moral law, but also as charged with a special oversight of the moral foundation of human life. He describes this oversight in both negative and positive terms.

First, in a negative way, civil government serves the moral order by discouraging evil, and specifically by punishing people who do evil things. In doing so, it is not inspired solely by political or economic purposes. It functions, rather, as the proper political agent of sanctions supportive of the moral law. For example, the government throws bank robbers in jail, not because bank robbing is harmful to the economy, but because the bank robber violates the moral law in a very serious manner. The government punishes murderers, not because murder adversely affects the census report, but because the murderer violates the moral law in a very grave way. It is precisely to vindicate moral principle that the civil authority possesses the jus gladii, and “it does not bear the sword in vain” (Romans 13:4). This truth seems obvious enough to everybody but anarchists.

Our assertion here does not mean, obviously, that the sanctions of civil law should cover every conceivable moral situation, and certainly there is no proper execution of civil justice apart from political prudence, even wisdom. We do mean, however, that the sanctions of civil government are not arbitrary; they are, and in principle must be, buttressed by the moral law and presuppose a moral foundation. That is to say, it is certainly a function of government to “legislate morality,” not in the sense of establishing the moral law by its legislation (for that would put Caesar in the place of God), but by consulting moral principles in the crafting of that legislation.

Second, in a positive way, civil government serves the moral order by encouraging the good. “Do what is good and you will have praise from the same,” wrote St. Paul, thereby affirming the pedagogical value of civil law. Government does not exist solely for the restraint of evil, but also for the advancement of the good, appreciating and fostering such things as tend to improve the moral existence of men. Good government, in short, will not only respect conscience; it will endeavor to inspire and to inform conscience.

There are various ways in which civil government is able to encourage the good, but the power of taxation is arguably chief among them. This has ever been well understood in American society and explains why, for instance, American governments have always thought it unseemly to tax religious organizations. The latter policy rests on the common assumption that religion, insofar as it turns man’s mind to eternal truths, including the truth of the moral law, is very good for the public weal.

For the same reason, the tax code also laudably embodies a special respect and concern for the married state, the latter being the foundation of civil society itself. On the other hand, for the tax code to extend a comparable respect to the households of homosexual unions would be a most serious perversion, because it would encourage moral evil, and moral evil is never in the best interest of society. It is already an arduous thing, after all, that prudence may require the civil order to tolerate some measure of moral evil; it should never be required to reward moral evil.

These are the sorts of considerations, we believe, that should preoccupy American Christians during this year of especially intense political interest, culminating in the important political verdicts to be rendered this coming autumn. It is high time, in short, for Caesar to reassess and rise to his moral responsibilities.

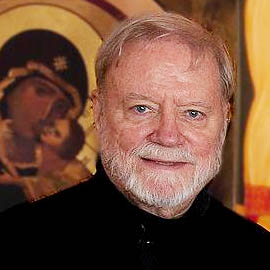

Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church in Chicago, Illinois. He is the author of Christ in the Psalms, Christ in His Saints, and The Trial of Job(all from Conciliar Press). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

“Caesar & Conscience” first appeared in the May 2004 issue of Touchstone.