A visit to the Byzantine Monastery of Myrelaion, in Constantinople (Theodoros Boufidis)

25 Σεπτεμβρίου 2016

There are neighborhoods in Constantinople (now, Istanbul, Turkey) which, although oversighted, are full of particularities, of hidden beauties and of glorious history. Vlaga (or Laleli) is one of those neighborhoods, and every time I pass over there I find novelties and my heart fills with strong feelings. This time I had the joy to visit the Byzantine Monastery of Myrelaion and a part of the nearby palace, built by Emperor Romanos Lekapenos in the 10th century.

Main church of Myrelaion Monastery, today Bodrum Camii Mosque

Myrelaion Monastery is one of those Christian churches converted into mosques. Every time I visit such places I feel my heart in anguish, but I also sense some uncertainty, because you never know in what degree the initial building suffered alterations. The name of the current mosque is Bodrum Camii.

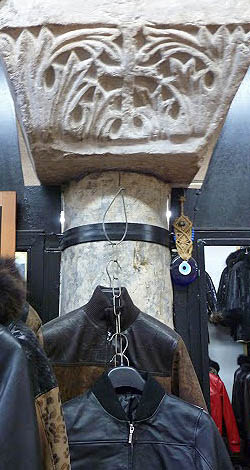

Just a few meters before the entrance of the former monastery, my sight was attracted by a giant advertising panel that read “Myrelaion.” With my curiosity aroused, I went over there and I saw an inconspicuous small entrance. Descending a few steps, I found myself in a huge circular space: the old rotunda, once the palace cistern. However, nowadays it accommodates a clothing bazaar.

A space like that, at first, causes dismay and heartache

Byzantine capitals with sculpted crosses and contemporary fur coats

This rotunda was built somewhere in the 5th century and the historians are yet unable to determine its initial function. It has a huge dome and an outer diameter of almost 42 meters, being the largest rotunda of Roman-Byzantine era. Only the Roman Pantheon had a larger dome.

During the rule of Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos (10th century) it suffered some alterations, caused by the future adjacent construction of Myrelaion Monastery. Adding 74 extra columns, the Emperor transformed the rotunda into one of the eight cisterns of Constantinople.

During the rule of Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos (10th century) it suffered some alterations, caused by the future adjacent construction of Myrelaion Monastery. Adding 74 extra columns, the Emperor transformed the rotunda into one of the eight cisterns of Constantinople.

During the years of Ottoman yoke, this space wasn’t used very differently than in our days. It accommodated fish markets, workshops, distilleries, steam baths and warehouses until early 1900s, when the site and the surrounding area became a dump. The archaeologists begun to excavate this area in 1930s, and they brought to light the circular cistern and the palace of Emperor Romanos Lekapenos. Then, after several failed attempts of restoration and redevelopment of the space, in 1993 it became a bazaar.

The merchants assumed I was there for their leather coats, so they started to come around me, trying to lure me with their offers. At that moment I thought about the bad example given by those tourists who visit Constantinople just to buy fur, leather coats and such, neglecting or totally ignoring many other key aspects of the City.

As I left the cistern behind me and went up to the monastery, I thought that, after all, no matter how much the City would change, no matter how many new names it will acquire, no matter how many new buildings will be erected, no matter how many attempts will be made to keep into oblivion the marks of the “other” city – there will always be everywhere enough testimonies to resist this attempt of distortion.

Climbing the stairs, I faced the beautiful monastery, with its distinctive architecture, typical to that Byzantine age: a smaller dome, which doesn’t touch directly the main structure – the two architectural elements being joined by a cylindrical tympanum. The outward niches girdling the church bestow harmony and elegance on its external appearance.

The monastery endured much destruction and it was eventually abandoned after the fire of 1911, resting half-buried into the ground, beneath earth, rocks and rubbish. Archaeological excavations began in 1965, with the purpose of digging up the monastery. In 1986 the monastery was restored and in the next year it was reopened as a mosque, retaining this purpose until this day.

The right-shifted mihrab testifies about the original function of the building

At first sight, the interior of the church looks like an ordinary mosque. Only the right-sided positioning of the mihrab indicates the Christian origin of the building. On a closer look, the trilobated sanctuary with its three independent domes becomes evident, and so does the cross formed by the four crossed arches which support the Byzantine dome.

The central axis indicates the fact that we have here is Christian ecclesiastical architecture

Just as I thought that my visit to Myrelaion Monastery was about to end, I was approached by the Imam. At first it seemed a trivial conversation, but soon he offered to show me the underground crypt, namely the former secondary church! Not every visitor has this privilege, so I was greatly enthusiastic.

Perhaps the monastery built by Emperor Romanos in 920 AD was meant to a convent, but definitely the Emperor also had other purposes in his mind. Usually the Emperors were buried in the Monastery of the Holy Apostles, but Romanos ascended to throne in a less honest way, so presumably he wouldn’t have been buried there. Therefore he found another burial place in Myrelaion Monastery.

Depiction of Emperor Romanos Lekapenos’ Palace and of Myrelaion Monastery’s main church

In 922 AD, Empress Theodora was buried here and, subsequently, her children. The earthly remains of Emperor Maurice and of his family were also transferred there. A total of nine tombs – emperors, empresses and members of their families – were under my feet.

The secondary church, located beneath the current mosque

The Imam indicated me the spots of the first excavations, where the teams of archaeologists began to dig tunnels to enter the church. Initially, crypts and hallways were co-joining here the two levels of the church with the rotunda and the palace. He also showed me where was the level of the soil that buried the building – indeed, at some point in time, the monastery was almost entirely covered by earth.

The ground level was above the second window. Archaeologists had to dig tunnels to enter the church

I walked several times over every inch of space, and as I was near one of the columns, I felt a slab moving under the carpet. I shuddered at the thought that maybe I stepped over one of the Byzantine Emperors’ graves.

A beautiful Corinthian capital, probably older than the church itself

After such destruction and desolation, the place where once was the sanctuary treasures now only one preserved fresco. The fresco depicts Empress Theodora kneeling with her arms open and praying to the Mother of God, Who has her right hand reaching towards the Empress and her left hand holding Christ the Savior.

Christian fresco from the former sanctuary

Although initially I was scandalized to see the rotunda became a bazaar, nevertheless I must appreciate the work of Mr. Mustapha, the archaeologist who, back in 1987, made many efforts to preserve the monument. Certainly, most of us will be sad to see the church transformed into a mosque, but that may be the only reason for this building to be still standing. I tremble when I imagine the monastery 100 years ago – a garbage dump, buried under earth and rocks…

Just before I leave Vlaga, I turned around to catch a final glimpse of Myrelaion Monastery. There are many who claim this is an architectural copy of legendary Nea Ekklesia – it is undoubtedly one of few remaining examples of Macedonian Dynasty’s ecclesiastical architecture. This architectural style gained a new period of flourishing only after the fall of Constantinople and later became the constructive template par excellence of the Byzantine churches. Therefore, I visited one of the original buildings of this architectural style – and, leaving aside certain disappointments and dilemmas, I said a deeply moved farewell to Vlaga neighborhood.