Death in Late Antiquity and its origins, according to the Orthodox faith (Maria Dimitriadou, Pedagogue)

11 Δεκεμβρίου 2016

[Previous post: http://bit.ly/2g74nuc]

1.3. Late Antiquity

A very different philosophical position on the origin of the soul was held by Epicurus (341-270 B.C.) and his adherents, who believed in transplantation. For the materialist Epicurus, the newly-born child was merely a transplant of the soul of its parents, that is simply the fruit of their union, not a creation of God. Death, then, dissolves the soul, which is no more than a collection of molecules, and eradicates all human feeling. With this reasoning, we shouldn’t fear death, because we won’t feel it. Instead, we should enjoy the pleasures of life while we can. Epicurean philosophy is considered to be the foundation for later materialist and atheist approaches.

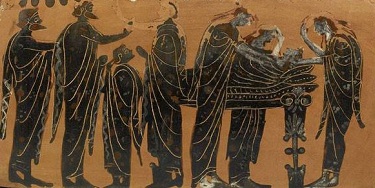

Another typical current of thought in the philosophy of Late Antiquity was formulated by Stoic philosophers such as Zeno of Citium (336-264). Cleanthes the Stoic (304-233 B.C), Chrysippus (281-208 B.C.) and Epictetus (50-138 A. D.). They followed the philosophy of pantheism, believing that the soul is a fragment of the world, that is it’s material, and is dissolved after death in the cosmic fire, which is the fate of all beings. Moreover, the Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius (121-180 A.D.), heavily influenced by Aristotle, considered both the soul and body to be corporeal and mortal. He distinguished only the intellect, as a fragment of god, with a mental and immortal nature, which, after death, returns to the divine. The Stoics, therefore believed in some kind of divine providence and some purpose in this present life.

In general terms, no matter how hard they tried to deal with death and remain unmoved by it, people in the ancient world felt an emptiness in their soul and were overwhelmed with anxiety, sorrow, fear and doubt. Nevertheless, God granted them, even in the pre-Christian era, a small insight into the truth. In the years which have followed, personalities who have operated in the realm of non-Christian philosophy have continued to be troubled by similar feelings. People such as today’s existentialists, who try to manage death by ignoring it. But as Socrates rightly pointed out, investigation into this inevitable event is the beginning of all philosophy. As regards the mystery of death, though, it is to be expected that the theories would be imperfect and would present obscurities, contradictions and ambiguities without divine Revelation.

2. DEATH VIEWED ACCORDING TO THE ORTHODOX FAITH

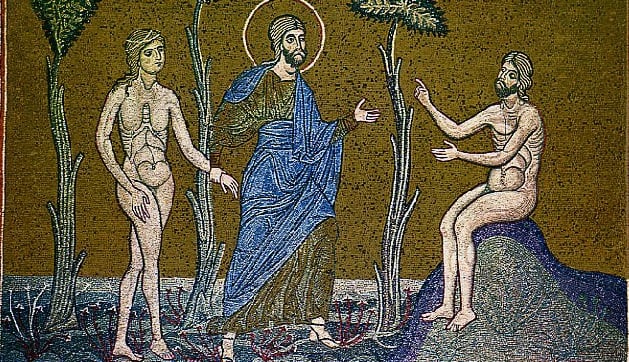

The Christian view of the soul and death was formed through the symbolic and sacramental words of the book of Genesis, then completed and confirmed by the revelatory teachings of the New Testament. The enlightened Fathers of the Church have produced an enormous and rich literature which, among various other issues, also investigates the mystery of death. Thus, we’re given the opportunity to delve further into it and to find the springboard for overcoming it.

2.1. Death’s entry into the world

According to Holy Scripture and the Fathers, death does not have its source and origin in the divine will. God made us capable of receiving both mortality and immortality. Unlike the rest of the creation, Adam wasn’t born to die, but to become immortal through his own free will. If Adam and Eve, with the innate potential they had for immortality, had conformed willingly and without coercion to the divine will, and had in this way set their will firmly on what is good, they’d have achieved immortality and wouldn’t have tasted death. By practicing virtue, they’d have been able, by grace to achieve ‘the likeness’ of God and to live with Him, the source of life, for eternity. Although they were aware of the consequences, they violated God’s commandment. Through their disobedience and lack of repentance, they themselves – as do we- became the cause of their death and the loss of the bliss of Paradise.