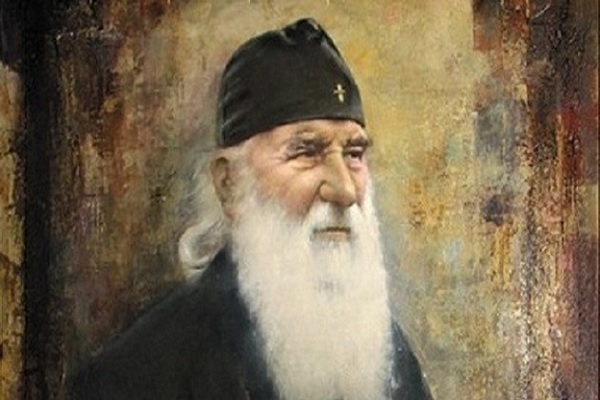

Saint Justin Popović, a great monastic figure (Athanasios Gieftits)

16 Ιουνίου 2017

Saint Justin Popović, (14 June)

The holy and God-bearing Father Justin the New, from the Monastery of Ćelije (the Holy Archangels), was born on 25 March 1894, on the morning of the Annunciation, in the town of Vranje in Southern Serbia. His father was a priest called Spyridon and his mother was Anastasia. At baptism he was given the name Blagoje [for the feast of the Annunciation]. His father came from a long line of clerics which had given the Orthodox Church at least seven priests, as can be seen from his surname ‘Popović’, meaning ‘son of a priest’. Even as a child he often went with his parents to visit the nearby Monastery of Saint Prohor at Pčinja, where, in 1929, he witnessed the cure of his mother, who had been suffering from a serious illness. It was she who taught him Gospel piety, prayer and fasting.

A second source of devotion for young Blagoje was his study of the Gospel, from when he was fourteen, and his ascetic way of life, which he continued until he died. He set himself the rule of studying three chapters of the New Testament every day and continued to do so throughout his life. From an early age he was concerned about how he was to gain eternal life. As he grew spiritually, he lived and breathed the atmosphere of the Holy Scriptures.

The third source of divine inspiration for him was reading the Holy Scriptures and, later, the works of the Fathers of the Church. The saints of God, who are the living likeness of Christ, were his constant and daily guides and teachers. This is why he remarked: ‘Christians today can be true Christians only if they’re guided, day by day, by the saints of God’. He particularly loved Saint John Chrysostom, to whom he prayed with sincerity and sweetness in his childhood. He gave himself over completely to Christ, his guides being the holy Fathers, the saints of God, whose Lives he later wrote and translated, as well as their struggles and their God-given Orthodox philosophy and theology.

In 1905, after he’d completed the four classes of primary school, as an excellent student, he went to the nine-year school of Saint Sava, in Belgrade, having passed the examinations with top marks. He continued to be a first-class student throughout his time there and was fortunate in having the enlightened Saint Nikolaj Velimirović as a teacher. During the course of his studies he became interested in philosophy, paying special attention to the works of Dostoevsky, through which he became aware of the nihilism and self-centredness of human wisdom without Christ. A burning love for Christ was kindled in his heart which remained unquenched until his last breath.

He left school in 1914, but was then caught up in World War I and drafted as a medical orderly. He followed the fortunes of the Serbian Army and took the path of exile, through the mountains of Albania, towards Corfu. On the way, he felt that he was now ready to dedicate his life to Christ, and, with the blessing of Metropolitan Dimitrije of Belgrade, he took monastic vows in Skandra, on 1 January, 1916, being given the name of Saint Justin, the martyr and philosopher.

From Corfu, on the initiative of Metropolitan Dimitrije, he left with a group of other theologians to pursue theological studies in Petrograd [Saint Petersburg]. Because of political developments there, however, he was soon forced to leave and went to Oxford. He stayed two years, writing his doctoral thesis on The Philosophy and Religion of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. His insistence on his critique of Western Christianity and his defence of Dostoevsky, however, meant that his thesis was not accepted. The last chapter of this thesis presented a very caustic critique of the shallowness and hypocrisy of Western anthropocentrism and humanism, particularly that of the Church of Rome. In 1919, then, at the end of the war, he returned to Serbia and was appointed teacher of theology in Sremski Karlovci. Soon afterwards, with the blessing of the Patriarch of Serbia, he headed for Greece, ‘in order to become more Orthodox’, as the Patriarch said. He remained in Athens from 1919 until May 1921, and took his doctoral degree in 1926 with a thesis entitled ‘The problem of the person and knowledge in Saint Makarios the Egyptian’. His two-year stay in Greece was of great benefit and importance to him personally, and also for his later work with churches in Serbia. He became closely acquainted with the centuries-old piety and the active Church-life of the Greek people and, in the last days of his life, he told the Serbs: ‘Always love our brethren the Greeks as your spiritual parents and godparents, as your constant teachers in the faith, in devotion and in Church attendance and involvement’.

He knew Old Slavonic very well, and also Ancient Greek, Latin, Russian, Modern Greek, English, French and German.

In the years that followed, he worked in Church Schools in Karlovac, Prizren and Monastiri (Bitola). In 1930-31, the Serbian Church sent him, together with Metropolitan Iosif, on a mission to Czechoslovakia. They worked together for a year there, educating and organizing parishes and the monastic life of the Orthodox Slavs of Carpathia who had returned to Orthodoxy after their association with the Uniates. While he was still there, he was elected Bishop of the newly-created see of Carpathia [Eparchy of Mukačevo and Prešov], but out of humility did not accept the position.

During the German Occupation, he lived in various monasteries, then gradually moved to Belgrade, sharing the fate of his people. When the new Communist regime was established in 1945, he was expelled from the University of Belgrade, together with another 200 teachers. He was soon placed under arrest in the Monastery of Sukovo in Pirot in South-Eastern Serbia and was imprisoned (1946). He was almost executed by the state as an ‘enemy of the people’, but was saved at the last moment when Patriarch Gavriil, on his return from Auschwitz, demanded his release.

Expelled from the university, without any pension, deprived of all human, religious and political rights, he lived basically as a hermit in the small convent of the Archangels at Ćelije, in Valjevo. But even there the civil authorities wouldn’t leave him in peace. Apart from the constant, oppressive surveillance, there were frequent interrogations by the civil administration in Valjevo. At a time when the Holy Synod was meeting in emergency sessions in Belgrade, he was forbidden to leave the monastery for months, in case he influenced the bishops. Despite these difficult and painful conditions, he continued his unceasing prayer and maintained contact with those who were brave enough to visit him. He continued his missionary work and his writing, never neglecting the study of his beloved Fathers and the Lives of the Saints.

He celebrated every day, fasted completely all the Fridays of the year, as well as the first week of Lent and Great Week, while he also kept other fasts apart from those ordained by the Church. Following the centuries-old monastic rule, he completed all the services of the twenty-four hours. He commemorated hundreds of names at the Divine Liturgy, names which he’d been given by word of mouth or by letter.

Despite the severe restrictions placed upon him by the civil authorities, his renown spread quickly and extended beyond the borders of Serbia. He was visited not only by Serbs from all over the country, but also by many Greeks. He fell asleep in the Lord on 25 March, 1979, the day of the Annunciation, which was also his birthday. Since his canonization, his memory is celebrated on 14 June.