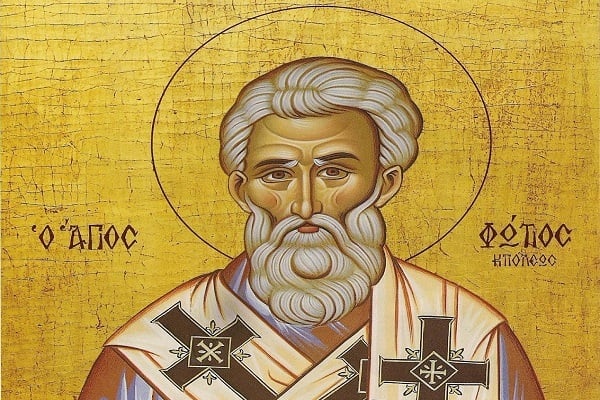

The Life and Work of Fotios the Great (Agapi Papadopoulou, Theologian)

1 Νοεμβρίου 2017

[Previous post: http://bit.ly/2yWnJex]

1.1 The Life and Work of Fotios the Great

Fotios (Photius) the Great (810-893) was born in Constantinople into a rich, aristocratic family. His father was called Seryios (Sergius), a genuinely Orthodox man, as Fotios himself would later say, and his mother was Eirini (Irene) a virtuous and godly woman. His mother’s brother had married the sister of the Empress Theodora, who supported the veneration of icons, and his father’s brother was Patriarch Tarasios of Constantinople. Fotios received an excellent education and devoted himself to the study of the Classical Greek and Patristic literature. During the second period of the iconoclast controversy (815-843), Fotios’ family suffered persecution for their support of the icons and Fotios himself was excommunicated because of his attachment to their veneration. After the triumph of Orthodoxy, however, in 843, and the final restoration of the icons, he was restored to the communion of the Church and, in the reign of Emperor Michael III (842-867), was appointed to a variety of offices at court.

Despite his increased responsibilities as a highly-placed public functionary, he continued to be fond of studying and spiritual investigations. His reputation as a learned scholar seems to have attracted a good number of keen young men and Fotios maintained a circle of select students, whom he taught at home. In 847, Patriarch Ignatios had ascended the throne. He was a man who had been castrated and obliged to take the monastic habit at a young age. His election, which took place during the reign of Theodora, pleased the powerful Studite monks, because, as a monk himself, Ignatios shared their views. Later, however, when the political regime changed, with the promotion of General Vardas to the rank of Caesar and the undertaking of initiatives by Michael III, who had now come of age, co-operation between the political leadership and the Patriarch became fraught. The reason was the support given by Vardas to the party opposed to Ignatios, which considered that the latter’s election, although accepted, had been strongly influenced by Theodora. The final rift came when Patriarch Ignatios acted hastily and gave credence to slanders against Vardas, which accused him of immoral behaviour with the widow of his son. As a result Vardas was excluded from Holy Communion.

This open conflict coincided with the coming-of-age of the young emperor, Michael III, which strengthened the hand of Vardas. When the opportunity presented itself, he accused Ignatios of organizing a plot and forced him to vacate the Patriarchal throne. A new Patriarch had to be found and Fotios was thought to be the most suitable candidate, given that he was most powerful intellect of the age, an excellent politician and a most able diplomat. After much hesitation, Fotios eventually agreed. From being a layman he was promoted through all the degrees of rank of the clergy in five days and was declared Patriarch on December 25, 858. The situation was fragile because of the constant challenges to Fotios on the part of supporters of Ignatios. So the focus of the clashes became the legitimacy of Fotios’ election. The supporters of the former Patriarch, headed by the monks of the Monastery of Studion, sought the intervention of Pope Nicholas, who, in turn, exploited the opportunity to increase the influence of the Western Church in the resolution of Church matters.

In the same year as Fotios became Patriarch of Constantinople, Nicholas I (858-867) became Pope of Rome. When Fotios sent a letter to the Pope informing him of his installation, Nicholas decided that, before recognizing him, he would like to follow more closely the clash between the new Patriarch and Ignatios’ circle. So, in 1861, he sent legates to Constantinople. Fotios wanted to avoid fresh conflicts, and received the legates with respect, inviting them to attend the Synod which had been called in Constantinople with the aim of settling the issue which had arisen between him and Ignatios. The legates agreed and, with the rest of the Synod, came to the conclusion that Fotios was the legitimate Patriarch. When they returned to Rome, however, Nicolas declared that they had exceeded their authority and rejected their decision. It is clear that Nicholas was of the opinion that the regime of Ignatios was more kindly disposed towards him and would serve his interests better. So, two years later a council met in Rome which exonerated Ignatios and condemned Fotios. This blow, together with the heightened claims of the Papacy in Bulgaria, forced Fotios into retaliation. He was unable to call into question the election of Nicholas, and was thus obliged to move the whole issue onto the dogmatic level, in particular to a discussion of the filioque. In 867, then, Fotios took action. He wrote an Encyclical Letter to the other Patriarchs of the East, denouncing the filioque and those who had adopted it. After the letter had been sent, Fotios convened the Synod of Constantinople (879-880), which excommunicated Pope Nicholas, calling him a heretic.