In Honour and Memory of Archimandrite Placide (Deseille) Simonopetritis

17 Ιανουαρίου 2018

On 11 January, the funeral was held for Archimandrite Placide Deseille at the Holy Monastery of Saint Anthony the Great in Saint Laurent en Royans, France, a dependency of the Holy Monastery of Simonos Petras on the Holy Mountain, where Père Placide had been tonsured as an Orthodox monk. He had fallen asleep in the Lord on 7 January, aged 91.

His Eminence Emmanouil, Metropolitan of France, officiated and the service was attended by hierarchs of other Churches.

Also present were representatives from the mother monastery of Simonos Petras and nuns from the women’s monastery of the Annunciation of the Mother of God, in Ormylia, Halikdiki.

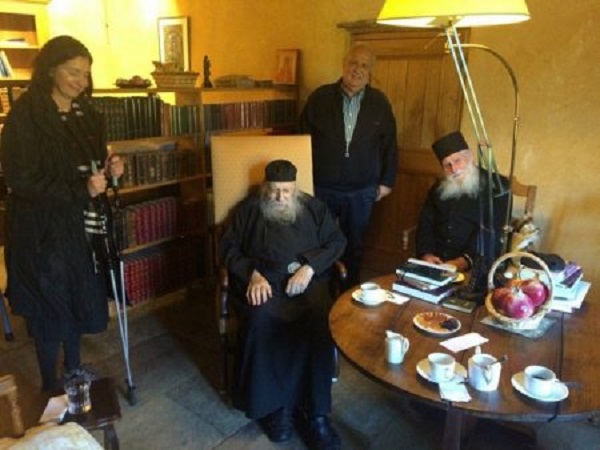

Photo: Dr. Stefanos Dimopoulos

Père Placide was an outstanding French Roman Catholic cleric and theologian, who after a long and taxing spiritual quest, entered the Orthodox Church in 1977. From then on, through his close spiritual relationship with Elder Aimilianos (the then Abbot) and the brotherhood at Simonos Petras, he dedicated his life to transplanting the monastic and hesychast tradition of the Holy Mountain to the soil of France.

Here at Pemptousia, we have recently published texts from his interpretation of the Song of Songs.

The following extracts are from his book The Orthodox Church and the West.

‘While it’s my purpose to speak this evening about the Orthodox Church in the West*, I will refer mainly- though not exclusively- to France, since I know less about the circumstances which obtain in other countries in Western Europe.

The Orthodox Past of the West

Despite appearances, the presence of Orthodoxy in the West is neither new, nor something brought in from the outside. Besides, there’s nowhere where the Orthodox Church is unknown, since it’s the Church of Christ and catholic (i.e. universal) in its essence.

Moreover, the Orthodox in France and in the West are deeply aware that they’re reconnecting with the very roots of their land and their culture.

We should never forget that the West was, in fact, Orthodox for a thousand years, until the dismal schism of the 11th century, though the omens of this separation were there from the time of Charlemagne.

Innumerable Orthodox saints lived in the West, from the Apostolic Age to the dawn of the Middle Ages. Many French villages bear the name of saints who, though they were neither apostles nor martyrs, were universally honoured throughout Christendom. Almost all of them lived in the Gallo-Roman or Merovingian eras and, therefore, before the 11th century. The lives of these saints are precisely the same as those of all the Orthodox saints with whom we’re familiar. As well as this, the West also had Fathers of the Church, recognized as such by the whole of Orthodoxy. To mention only some of the greatest, there were Popes Leo the Great and Gregory the Great (the Dialogian) in Rome and Ambrose of Milan and Saint Hieronymus in Italy. The Gauls had Saint Irenaeus of Lugdunum (Lyons), Saint Hilarion of Poitiers and Saint Cassian of Marseilles. Alas, the West then rather forgot them and subscribed almost exclusively to the school of Saint Augustine, the great teacher of Christian Africa. Augustine is an exceptional saint and a great genius of Christianity, but his thought, which at times is intensely personal, ought to have been balanced and complemented by the contribution of all the other Fathers, particularly the Greeks. Excessive reference to Saint Augustine alone is certainly a contributing factor in the later severance of the West from the rest of the Christian world. We can say that, in large part, both Roman Catholicism and Protestantism are Augustinian.

We’re reminded of the Orthodox roots of the West by the numerous monuments, some of which, at least, go back to that era. There are lots of these monuments in Italy, pilgrimage sites which bring to mind this ancient Christianity better than the catacombs and the remains of ancient Roman basilicas. In France, there are still baptistries and places of worship from the 5th century, such as the chapels on the Lérins Islands or the remains of the sacellum of Saint Cassian in Saint Victor’s Marseilles. Spain has preserved wonderful buildings from the time of the Visigoths, while in Germany, the whole of the Rhineland region is rich in remains which date back to this ancient period.

A severe breach occurred in the 11th century, the consequences of which quickly became apparent. It would be no exaggeration to say that, at the turn of the 11th century, a leading Frenchman would have felt closer to a 5th century Christian from Asia Minor than with another French Christian from two centuries later. While the Romanesque architecture and the wall-paintings of the 6th and 7th centuries are still quite close to those of the Orthodox world, the Gothic art which followed in the 13th century followed very different paths. While the theology and spiritual teaching of the Benedictines and Cistercians of the 11th and 12th centuries belong, in large measure, to the sphere of the Fathers of the Church, the Scholastic theology and new spirituality which replaced them during the second period of the Middle Ages differ greatly.

And yet, the change was not all-encompassing. Thomas Aquinas, for example, wanted to be more a disciple of the Fathers than of Aristotle: real knowledge of Saint Dionysios the Areopagite, Saint Gregory of Nyssa and other Greek Patristic texts enabled him to express important matters differently from the almost exclusive Augustinian manner of his predecessors, although from other points of view, he remained dependent on him. From the end of the 13th century, men in the Rhineland and Flanders who were interested in spiritual matters- and we should add the Spaniard John of the Cross to their number- formulated a spiritual teaching significantly inspired by the works of Saint Dionysios the Areopagite. Vladimir Lossky would later be particularly interested in Meister Eckhart. In the 17th century, in France, a spiritual school formed around Cardinal de Berulle, which rediscovered, in part, the teaching on deification which was formulated by the Greek Fathers. Also in France, at the same time Père Lallemant and his disciples preserved a teaching on ‘guarding the heart’ and obedience to the Holy Spirit which is not unlike the hesychast tradition. Besides this, still in the 17th century, a huge number of translations and publications of works by the Fathers of the Church were made and this would continue through the 19th with the monumental publication of the two Patrologia, the Greek and Latin, by Abbé Migne, an effort which extended into the 20th century with the 300 volumes of the Sources Chrétiennes. Some of those best acquainted with the thought of one of the greatest French poets of that century, Charles Péguy, underline the similarity of his views to Orthodox teaching. We could cite many more such examples.

Naturally, we should be careful not to overstate the similarities. None of these authors and none of their works are truly Orthodox. But they all bear witness to certain features which survived and to a kind of nostalgia for ancient Orthodoxy. For Catholicism, with its basis of the theory of dogmatic evolution, the Fathers of the Church and the Christianity of the first centuries represent an interesting, but outdated stage in the life of the Church. Father Hans Urs von Balthasar** whimsically stated that ‘The texts of the Fathers are the Church’s newspaper when it was seventeen years old’.

Be that as it may, the French Orthodox can interpret these elements which have survived in another way. By replanting the Orthodox Church in the West, they’re aware that they’re reconnecting with their roots and that they’re bringing to fruition a seed that’s remained a hidden presence in all that is best in what the spiritual life of the West has produced.