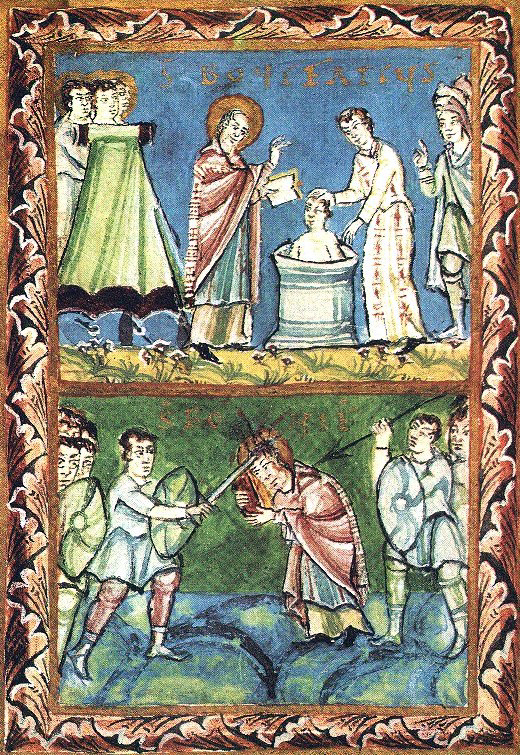

The advent of Orthodoxy in the German-Speaking lands (Part 1)

25 Ιουλίου 2010

Orthodoxy in the West

Many Western people—both Orthodox and non-Orthodox—identity Orthodoxy with national churches of Eastern European and Middle-Eastern origin. Those who live in Western lands with holy soil under their feet may not realize that beneath them rests a vibrant Christian legacy, which for many hundreds of years was identical in spirit and almost indistinguishable in practice from the Christianity of the East.

In the lands in which German is now spoken, Orthodox Christianity was present, to a greater or lesser extent, from the earliest days of the Faith until around the time of the schism in 1054. It is still possible not only to uncover it in old writings and archeological, artistic, and other studies, but also to experience its living presence by venerating holy relics in places where they have been preserved and honored, and by reading unembellished lives of saints written by immediate disciples.

The Coming of Christianity

The coming of Christianity to the German-speaking lands was a gradual process, spreading over 800 years. In the beginning of the first millennium A.D., much of Western Europe was populated by Celtic peoples. The Romans had conquered vast areas of the continent and begun to make inroads into «Germania,» where Germanic tribes settled around the same time. After the Romans were defeated at the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest in 9 A.D., they were unable to realize their ambition of conquering all of Western Europe. Forced to remain west of the Rhine and south of the Danube, they did not plant their civilization in much of present-day Germany, and this meant that the Roman territories received Christianity long before the Germanic ones, due to their greater accessibility.

It must be remembered that our modern-day German-speaking countries did not exist in the missionary period. It was in fact many centuries before population and boundary shifts, wars, and language development had done their work, resulting in a blend of Celtic, Roman, and Germanic peoples in the West who spoke Old French, and to the east, a number of kingdoms which spoke Old German, with Latin used only in church. It was several hundred years before Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Luxembourg, and Liechtenstein emerged with more or less their present boundaries.

Christianity on the Roman Frontier in the Age of Apostles and Martyrs (A.D. 33-300)

In the first three centuries A.D., Christianity spread out rapidly in all directions from Jerusalem. The first apostles and their followers transmitted what they had seen, experienced, and heard—the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ and His teachings. The hope this brought to those it touched, along with the way of life of the early Christians, in marked contrast to the life around them, was infectious. It spread first through family groups of Jews scattered throughout the Roman Empire, then one by one and family by family through various groups of Gentiles. It came to the parts of the Roman Empire which were known as Gaul (now France and the Rhine and Moselle regions of Germany), Noricum (southern Bavaria and northern Austria), and Rhaetia (Switzerland and parts of Germany) in the same ways.

There are hints in many places that disciples of the apostles were sent into or through these territories, although we have no written records of this. In Switzerland St. Beatus is said to have been baptized in Rome by the Apostle Barnabas and then sent on mission to Switzerland by the Apostle Peter. There are similar traditions that disciples of the Apostle Peter might have come to Trier and Cologne in the Rhine region.

Many Christians came to the Roman frontier in the lands we are discuss¬ing as part of the Roman army, or were Roman civil servants; others were merchants from Greece and Syria. As there were many Germanic soldiers (and even commanders) in the Roman army, some of these may also have adopted Christianity. The first recorded miracle in a German-speaking country resulted from the prayers of Christians in the Roman army. On June 11 in the year 172, in what is now northern Austria, the Roman army was trapped without water on a very hot day as they were fighting the barbarian Marka-manni and Quadi. The army was about to succumb to the heat when, in response to the prayers of Christian soldiers, God sent a storm which refreshed the Romans and frightened the barbarians, who were then soundly defeated.

Although the persecution of Christians was not as fierce in the West as in the East, there were periods of persecution. In 177 many were martyred in Lyons (France), and since there were almost certainly Christian communities in nearby cities along the Rhine, such as (German) Cologne and Mainz, it is quite possible that similar persecutions took place there as well. Persecution of Christians also occurred under Emperors Diocletian and Maximian at the beginning of the 4th century. Among those who gave their lives for their faith at that time were: St. Maurice and the Theban Legion, African Christians who were martyred in present-day Switzerland; members of the same legion stationed at various other places, including Cologne, Bonn, and Xanten (Germany); the Martyr Afra of Augsburg; St. Ursula, virgin-martyr of Cologne with her companions; and the Soldier-Martyr Florian and his forty companions in Lorsch (Austria).

The importance of these early martyrs in the spread of Christianity was enormous. As soon as Emperor Constantine ended the persecution of Christians in 313, churches were built over the resting places of the martyrs, and they became important places of pilgrimage. People flocked there for consolation and healing, knowing they had their own spiritual heroes in these blessed ones who had been martyred in their own land.

From Constantine to the Barbarian Invasions

At the beginning of the 4th century, the young Church was vibrant in terms of faith, but small in numbers. It was represented in every city in the Roman Empire, but met for the most part in house churches and was materially poor—its clergy often had to support themselves at secular jobs. This was to change under Constantine. After he defeated Maxentius in 312 under the sign of the Cross, which he had seen in a vision, he ceased the persecution of Christians and began to support them. During his lifetime he granted liberty, subsidies, and immunities to the Church, and in 325 called the First Ecumenical Council at Nicea to establish unity among the Christians.

For a number of years Constantine, like his father before him, was the head of the western half of the Roman Empire, and had the city of Trier (Germany) as his capital. To this fact we owe the extraordinary spiritual treasures which we find in this city today. His mother, St. Helena, having journeyed to Pales¬tine and uncovered the True Cross, brought one of the nails of the Cross Saint Cassian the Roman. to Trier. It is believed that Bishop

Antiochus, whom she had called from Antioch to serve in Trier, added to the treasure by bringing the relics of the Apostle Matthias. The head of St. Helena herself rests there, as well as the sandal of the Apostle Andrew, the relics of St. Anna, mother of the Most Holy Theotokos, and the relics of many local saints.

Although Constantine did not force anyone to become Christian, Christianity grew rapidly under him and his successors. People were drawn by the holy example of the Christians and their warm mutual support. Further causes for conversion to Christianity were the influence of Christian spouses and the many miracles—especially of healing—which were performed through the prayers of the saints and petitions at the graves of the martyrs and ascetics. At the same time, however, some became Christians to curry the Emperor’s favor, realizing that baptism could be a passport to office, power, and wealth. Yet this was an impetus for one of the purest and most truly Orthodox movements of the time—that of early monasticism.

To be continued…