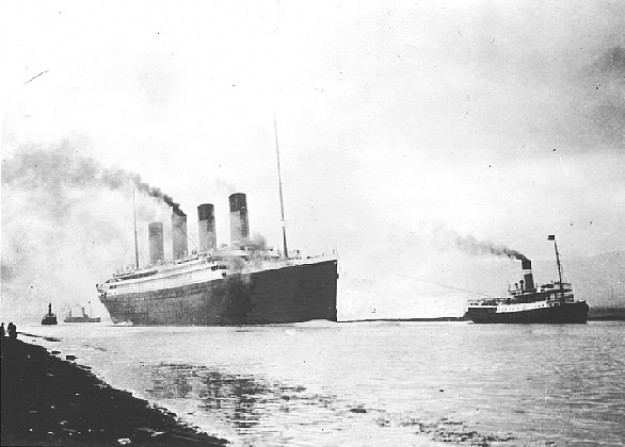

The Sinking of the Titanic, 1912

15 Απριλίου 2010

On April 10, 1912, the Titanic, largest ship afloat, left Southampton, England on her maiden voyage to New York City. The White Star Line had spared no expense in assuring her luxury. A legend even before she sailed, her passengers were a mixture of the world’s wealthiest basking in the elegance of first class accommodations and immigrants packed into steerage.

On April 10, 1912, the Titanic, largest ship afloat, left Southampton, England on her maiden voyage to New York City. The White Star Line had spared no expense in assuring her luxury. A legend even before she sailed, her passengers were a mixture of the world’s wealthiest basking in the elegance of first class accommodations and immigrants packed into steerage.

The Washington Post announces the disaster

She was touted as the safest ship ever built, so safe that she carried only 20 lifeboats – enough to provide accommodation for only half her 2,200 passengers and crew. This discrepancy rested on the belief that since the ship’s construction made her «unsinkable,» her lifeboats were necessary only to rescue survivors of other sinking ships. Additionally, lifeboats took up valuable deck space.

Four days into her journey, at 11:40 P.M. on the night of April 14, she struck an iceberg. Her fireman compared the sound of the impact to «the tearing of calico, nothing more.» However, the collision was fatal and the icy water soon poured through the ship.

It became obvious that many would not find safety in a lifeboat. Each passenger was issued a life jacket but life expectancy would be short when exposed to water four degrees below freezing. As the forward portion of the ship sank deeper, passengers scrambled to the stern. John Thayer witnessed the sinking from a lifeboat. «We could see groups of the almost fifteen hundred people still aboard, clinging in clusters or bunches, like swarming bees; only to fall in masses, pairs or singly, as the great after part of the ship, two hundred and fifty feet of it, rose into the sky, till it reached a sixty-five or seventy degree angle.» The great ship slowly slid beneath the waters two hours and forty minutes after the collision

The next morning, the liner Carpathia rescued 705 survivors. One thousand five hundred twenty-two passengers and crew were lost. Subsequent inquiries attributed the high loss of life to an insufficient number of lifeboats and inadequate training in their use.

End of a Splendid Journey

Elizabeth Shutes, aged 40, was governess to nineteen-year-old Margaret Graham who was traveling with her parents. As Shutes and her charge sit in their First Class cabin they feel a shudder travel through the ship. At first comforted by her belief in the safety of the ship, Elizabeth’s composure is soon shattered by the realization of the imminent tragedy:

«Suddenly a queer quivering ran under me, apparently the whole length of the ship. Startled by the very strangeness of the shivering motion, I sprang to the floor. With too perfect a trust in that mighty vessel I again lay down. Some one knocked at my door, and the voice of a friend said: ‘Come quickly to my cabin; an iceberg has just passed our window; I know we have just struck one.’

No confusion, no noise of any kind, one could believe no danger imminent. Our stewardess came and said she could learn nothing. Looking out into the companionway I saw heads appearing asking questions from half-closed doors. All sepulchrally still, no excitement. I sat down again. My friend was by this time dressed; still her daughter and I talked on, Margaret pretending to eat a sandwich. Her hand shook so that the bread kept parting company from the chicken. Then I saw she was frightened, and for the first time I was too, but why get dressed, as no one had given the slightest hint of any possible danger? An officer’s cap passed the door. I asked: ‘Is there an accident or danger of any kind? ‘None, so far as I know’, was his courteous answer, spoken quietly and most kindly. This same officer then entered a cabin a little distance down the companionway and, by this time distrustful of everything, I listened intently, and distinctly heard, ‘We can keep the water out for a while.’ Then, and not until then, did I realize the horror of an accident at sea. Now it was too late to dress; no time for a waist, but a coat and skirt were soon on; slippers were quicker than shoes; the stewardess put on our life-preservers, and we were just ready when Mr Roebling came to tell us he would take us to our friend’s mother, who was waiting above …

No laughing throng, but on either side [of the staircases] stand quietly, bravely, the stewards, all equipped with the white, ghostly life-preservers. Always the thing one tries not to see even crossing a ferry. Now only pale faces, each form strapped about with those white bars. So gruesome a scene. We passed on. The awful good-byes. The quiet look of hope in the brave men’s eyes as the wives were put into the lifeboats. Nothing escaped one at this fearful moment. We left from the sun deck, seventy-five feet above the water. Mr Case and Mr Roebling, brave American men, saw us to the lifeboat, made no effort to save themselves, but stepped back on deck. Later they went to an honoured grave.

Our lifeboat, with thirty-six in it, began lowering to the sea. This was done amid the greatest confusion. Rough seamen all giving different orders. No officer aboard. As only one side of the ropes worked, the lifeboat at one time was in such a position that it seemed we must capsize in mid-air. At last the ropes worked together, and we drew nearer and nearer the black, oily water. The first touch of our lifeboat on that black sea came to me as a last good-bye to life, and so we put off – a tiny boat on a great sea – rowed away from what had been a safe home for five days.

The first wish on the part of all was to stay near the Titanic. We all felt so much safer near the ship. Surely such a vessel could not sink. I thought the danger must be exaggerated, and we could all be taken aboard again. But surely the outline of that great, good ship was growing less. The bow of the boat was getting black. Light after light was disappearing, and now those rough seamen put to their oars and we were told to hunt under seats, any place, anywhere, for a lantern, a light of any kind. Every place was empty. There was no water – no stimulant of any kind. Not a biscuit – nothing to keep us alive had we drifted long…

Sitting by me in the lifeboat were a mother and daughter. The mother had left a husband on the Titanic, and the daughter a father and husband, and while we were near the other boats those two stricken women would call out a name and ask, ‘Are you there?’ ‘No,’would come back the awful answer, but these brave women never lost courage, forgot their own sorrow, telling me to sit close to them to keep warm… The life-preservers helped to keep us warm, but the night was bitter cold, and it grew colder and colder, and just before dawn, the coldest, darkest hour of all, no help seemed possible…

…The stars slowly disappeared, and in their place came the faint pink glow of another day. Then I heard, ‘A light, a ship.’ I could not, would not, look while there was a bit of doubt, but kept my eyes away. All night long I had heard, ‘A light!’ Each time it proved to be one of our other lifeboats, someone lighting a piece of paper, anything they could find to burn, and now I could not believe. Someone found a newspaper; it was lighted and held up. Then I looked and saw a ship. A ship bright with lights; strong and steady she waited, and we were to be saved. A straw hat was offered it would burn longer. That same ship that had come to save us might run us down. But no; she is still. The two, the ship and the dawn, came together, a living painting.»

References:

Elizabeth Shutes’ account first appeared in: Gracie, Archibold, The Truth About the Titanic (1913), reprinted in: Foster, John Wilson (editor), The Titanic Reader (1999); Lord, Walter, A Night to Remember (1955); Davie, Michael, Titanic: The Death and Life of a Legend (1986).